We are recovering – The Teenager from being attacked, my much lesser incident of a twisted ankle.

We are recovering – The Teenager from being attacked, my much lesser incident of a twisted ankle.

Damned foot-drop.

I remember lying at the back of the works van, having fallen and thumped to the ground, thinking, ‘this is just not happening’. But it did.

Do you remember those falls you had as a kid? That sickening thud of the pavement rushing to meet your head? That’s what foot-drop is like. Of course, it’s ‘curable’, if you concentrate on every single step you take and will your feet to rise to the occasion.

But who has time for that? So I fall. I trip. I can trip over dust, cables, pavements.

And it brings me up short, and maybe not in the way you might think.

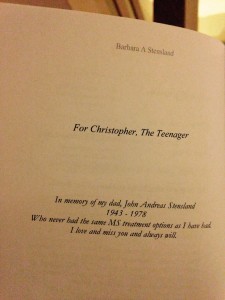

Our dad died forty years ago this year from complications arising from his MS; I am one of four siblings he left behind.

When he died in 1978, nothing was available to alleviate his condition; he was sent home after brutal tests, with only a walking stick and a diagnosis of ‘crippling paralysis’, now known as Primary Progressive MS.

After eight years, he died at the age of 35, a husk of the brilliant man and scholar he once was.

I am lucky. I was born into an age of MRI’s, MS nurses, disease-modifying therapies, which is why I didn’t hesitate to accept the one that would allow me to be well enough to be around long enough to see The Teenager in to University.

So when I come up against seemingly impossible situations, such as The Teenager calling me in work saying, ‘Don’t worry, but …’, I am perhaps more sanguine than most parents.

He is alive, well, and healthy. It is him who called me, not a consultant, a police officer or an anonymous University staff member. I was only grateful that I could speak directly to him, despite his trauma.

Christmas is always a tough time for families. The Teenager will be home in a week, and the washing machine will be pushed to its limit. The cat will be giddy with delight and I will be over the moon to have him back in our little cottage.

However, gratitude is the most important emotion; gratitude that I can greet him at the door, welcome him in and be the same person (plus limp) he last saw at University. His bed is ready with fresh linen, the fridge will be stocked and we’ll have a great catch up.

It’s precious. I’ll never lose sight of what we could have lost.

Father’s Day has always been difficult for me.

Father’s Day has always been difficult for me.